So that this kind of Absurdity, may rightly be numbred amongst the many sorts of Madnesse. (Hobbes, Leviathan, I.8)

That there are things or substances has always been the standing or falling proposition of Thomism, the only philosophy truly germane to that touchstone of Catholic faith—which is the dogma of transubstantiation. (Jaki, “Thomas and the Universe,” The Thomist 53.4, p. 567)

Pater Edmund writes, in a guest post at CosmosTheInLost, in answer to this question. This passage quoted below especially moved me, having found it to be an exacting description of my own experience:

I don’t deny that there are many hypocrites and rascals in the Church, who tarnish the splendor of the truth; I am one myself. But I have experienced again and again the victory of grace over human frailty in her. The holiness and unity and peace made within her, the forgiveness, the spontaneous unity among persons of all nations and characters. The mercy that I have myself received from through her, and which has helped me be a little bit less bad of person. As Don Julian Carron likes to say, “the victory of Christ is the Christian people.”

Pater Edmund rightly emphasizes in his reflections the centrality of living faith that shapes the vision of realities that surpass natural categories without contradicting them.

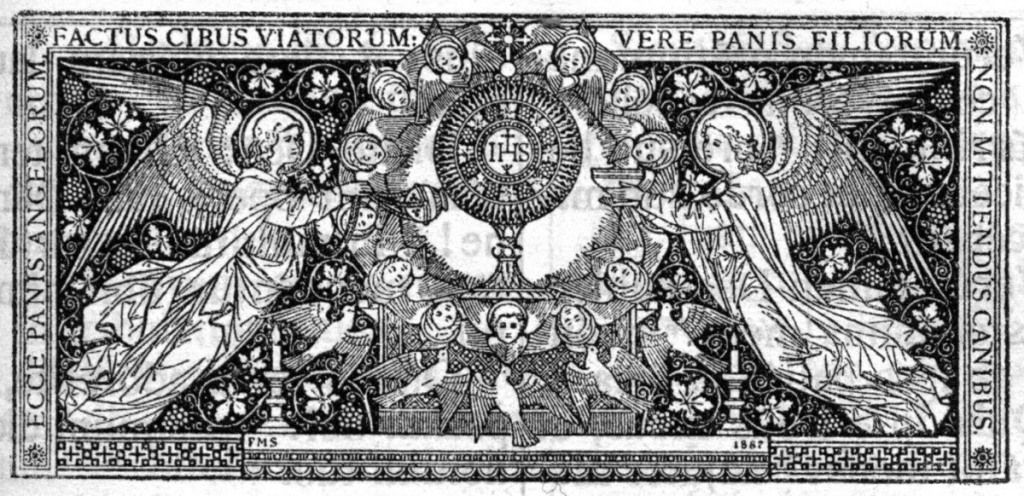

On this Solemnity of Corpus Christi, it is worth reflecting on the lengths to which the Catholic faith carries the believer.

Charles De Koninck notes in “This is a Hard Saying” that:

The perfect hiddeness of this sacrum secretum suits the perfection of the faith, says St.Thomas. Since God wishes us to participate in this divinity that no creature can know through its proper powers—no one has ever seen God (John 1:18)—is it not befitting that he demands of us a total faith in this Sacrament of the Way, the Truth, and the Life; a universal faith where reason removes itself from its dependance upon the senses, the source of its knowledge? Because our faith bears not only upon the divinity of Christ, but also upon his humanity by which he became like us so that we could become like unto him, is it not fitting to the very perfection of this same faith that in the Sacrament which contains substantially the very principle of all sanctification and which, in this perfect obscurity, announces in a manner so appropriate our union with him in the light of the future life, Christ shows his body and blood in an invisible manner? (p. 7)

The fittingness of this lowly veil covering not only Christ’s divinity (as did his humanity while on earth) but also hiding his humanity from us is a very difficult fittingness to grasp. It seems to demand far too much—it is a hard saying, who can accept it? De Koninck recognizes this.

It is, then, by a mercy truly unparalleled that God has deigned to meet us in perfect night and that, in order to elevate us to his own heights, he has satisfied for all our insufficiencies, he has asked in our act of faith an abnegation analogous to that of his Son. This is a hard saying; who can listen to it? (John 6:6) But is not the harshness of this saying for human ears the reason for us to adhere to it with a faith all the more firm? Is it not an admirable manifestation of the otherness of the divine truth having henceforward become “ours”? Instead, therefore, of being scandalized with his murmuring disciples, or intimidated by those who hold divine truth as scandalous, we have, on the contrary, every reason to cry out with St. Peter: Master, you have the words of eternal life! (p. 8)

Our senses see and report truthfully that we see accidents of bread and wine, but our highest faculty must yield to faith when, informed by faith, it denies that their substance is still present. The accidents remain, really existing, without their natural subject—a metaphysical aporia which many philosophers thought absurd (evidently, including Descartes), and which St. Thomas addresses perspicuously.

Indeed, the modern empiricists, tied up by accounts of knowledge that do not adequately relate the human intellect to its proper objects in reality, must deny all the more strenuously in the case of the Eucharist what their stories can barely accomplish in the case of sensible substances. Hobbes’ materialistic, mechanistic mind must write off as senseless all words which are unconnected to the singular instances or sets of atomistic motions based on our sense experience:

What is the meaning of these words. “The first cause does not necessarily inflow any thing into the second, by force of the Essential subordination of the second causes, by which it may help it to worke?” They are the Translation of the Title of the sixth chapter of Suarez first Booke, Of The Concourse, Motion, And Help Of God. When men write whole volumes of such stuffe, are they not Mad, or intend to make others so? And particularly, in the question of Transubstantiation; where after certain words spoken, they that say, the White-nesse, Round-nesse, Magni-tude, Quali-ty, Corruptibili-ty, all which are incorporeall, &c. go out of the Wafer, into the Body of our blessed Saviour, do they not make those Nesses, Tudes and Ties, to be so many spirits possessing his body? For by Spirits, they mean alwayes things, that being incorporeall, are neverthelesse moveable from one place to another. So that this kind of Absurdity, may rightly be numbred amongst the many sorts of Madnesse; and all the time that guided by clear Thoughts of their worldly lust, they forbear disputing, or writing thus, but Lucide Intervals. And thus much of the Vertues and Defects Intellectuall. (Hobbes, Leviathan, I.8)

Similarly, Locke, treating of the sources of error, notes that our minds develop a psychological inertia of various opinions planted by authority, even against the evidence of our senses.

The great obstinacy that is to be found in men firmly believing quite contrary opinions, though many times equally absurd, in the various religions of mankind, are as evident a proof as they are an unavoidable consequence of this way of reasoning from received traditional principles. So that men will disbelieve their own eyes, renounce the evidence of their senses, and give their own experience the lie, rather than admit of anything disagreeing with these sacred tenets. Take an intelligent Romanist that, from the first dawning of any notions in his understanding, hath had this principle constantly inculcated, viz. that he must believe as the church (i.e. those of his communion) believes, or that the pope is infallible, and this he never so much as heard questioned, till at forty or fifty years old he met with one of other principles: how is he prepared easily to swallow, not only against all probability, but even the clear evidence of his senses, the doctrine of transubstantiation? This principle has such an influence on his mind, that he will believe that to be flesh which he sees to be bread. And what way will you take to convince a man of any improbable opinion he holds, who, with some philosophers, hath laid down this as a foundation of reasoning, That he must believe his reason (for so men improperly call arguments drawn from their principles) against his senses? (Locke, Essay, IV.20.10)

Locke mistakes the function of reason—as if it is some bullheaded rationalism that makes the papists contradict their senses. Reason has no proper sway here, for it is faith alone that suffices.

This same faith, and motives for its credibility, are suspected by Hume:

The authority, either of the scripture or of tradition, is founded merely in the testimony of the apostles, who were eye-witnesses to those miracles of our Saviour, by which he proved his divine mission. Our evidence, then, for the truth of the Christian religion is less than the evidence for the truth of our senses; because, even in the first authors of our religion, it was no greater; and it is evident it must diminish in passing from them to their disciples; nor can any one rest such confidence in their testimony, as in the immediate object of his senses. But a weaker evidence can never destroy a stronger; and therefore, were the doctrine of the real presence ever so clearly revealed in scripture, it were directly contrary to the rules of just reasoning to give our assent to it. It contradicts sense, though both the scripture and tradition, on which it is supposed to be built, carry not such evidence with them as sense; when they are considered merely as external evidences, and are not brought home to every one’s breast, by the immediate operation of the Holy Spirit. (Hume, Enquiry, §10, pt. 1)

Of course, the “evidence” and “authority” brought to us by reason and the senses is insufficient even in the case of the testimony of the apostles. No mere reason or sensation can demonstrate commensurately the reality which the apostles encountered, even themselves, in faith. The Church is the present reality that permits us to touch that same Person. Besides: De Koninck unravels Hume’s sophistry:

Notice the cunning—conscious or unconscious—of Hume’s method. Not only does he destroy the species of miracles which are extrinsic motives of credibility in citing the ex- ample of a miracle which does not belong to that species, but he destroys, at the same time, the sacrament which is the most hidden, the most profound, and the greatest in the whole of the Christian life. He attacks the faith under its purest form, that by which we adhere not only to that which is wholly invisible as is the most Holy Trinity, but also, and firmly, to that which contradicts the principle and origin of all our knowledge: the senses. He chooses the case where the divine truth is most manifestly be- yond the intellectual knowledge which is based upon the senses. In the holy Eucharist, in effect, while the senses do not deceive themselves about their proper objects—they really are the accidents of bread and wine—it is nevertheless because of the senses that the intelligence, without faith, would fool itself as to the substance which is hidden under these accidents. (ibid., p. 6)

It is for these reasons that St. Thomas composes the following lines in the Adoro Te Devote. The reach of our entire range of natural powers must fall short of the Sacrament we adore. We must, for the sake of our salvation (Jn 6:53–59), believe something that is beyond the natural ambit of our very minds (a demand of faith made upon us, just as the trial of the fallen angels), submitting to that Truth the whole of our powers.

Seeing, touching, tasting are in thee deceived:

How says trusty hearing? that shall be believed;

What God’s Son has told me, take for truth I do;

Truth Himself speaks truly or there’s nothing true.