Over at Public Discourse, an essay by Joseph E. Capizzi and V. Bradley Lewis—entitled “Bullish on the Common Good?”—attempts to put recent conservative discussion about “the common good” in a more realistic and pragmatic light. They refer to C. C. Pecknold’s First Things essay, “False Notions of the Common Good” as well as two other essays that have garnered more notoriety: Marco Rubio’s “Common Good Capitalism and the Dignity of Work” and Adrian Vermeule’s essay “Beyond Originalism,” a defense of common-good constitutionalism.

Rubio and Vermeule’s themes are ancillary, however. A sign that Pecknold is the main interlocutor is that the essay is bookended, on the one hand, by a discussion of the old Thomistic controversy over the common good (discussed by Pecknold), and, on the other hand, a conclusion concerning the nugatory character of De Koninck’s debate with Jacques Maritain in light of contemporary Church teaching concerning the common good. Now, Prof. Pecknold is more than capable of defending himself. What follows are merely my reflections on the Cappizi/Lewis essay in view of my interest in the work of Charles De Koninck.

According to Capizzi and Lewis, in “False Notions” Pecknold “argues that our political debates need to be debates about the common good, but that a pervasive refusal of that idea has been an obstacle to the sort of public discussion we need.” This initial characterization is finalized by their conclusion: “Invoking the common good under the influence of De Koninck, Maritain, or even Aquinas doesn’t advance the political conversation that characterizes a healthy polity.”

However, it is unclear that the paraphrase of Pecknold is sufficiently accurate. In his essay, he writes that “This debate [between Maritain and De Koninck] is now largely forgotten, but we should revisit it, for it sheds light on our own political debates.” How so? After a review of the debate between Maritain and De Koninck—which, as both he and Capizzi and Lewis note, was only indirectly “between” De Koninck and Maritain—Pecknold observes:

Today, we struggle to have serious discussions about the common good—whether a common good conservatism, or constitutionalism, or the worker economy. This difficulty is rooted in the false notion of the common good under which we still labor. … To have a better dispute today about the common good, we must heed De Koninck’s counsel [concerning the primacy of the common good].

Furthermore, the current pandemic and its social limitations and suffering “has also opened up opportunities to speak about first principles again, to argue about true and false notions of the common good, and to insist that human dignity depends on God.”

“Hold on!”—you are saying—“That seems to be exactly what Pecknold was said to have argued.” Well, yes and no. Equivocation creeps in regarding exactly what it means to “debate the common good” and exactly what constitutes “a pervasive refusal of that idea.” How so?

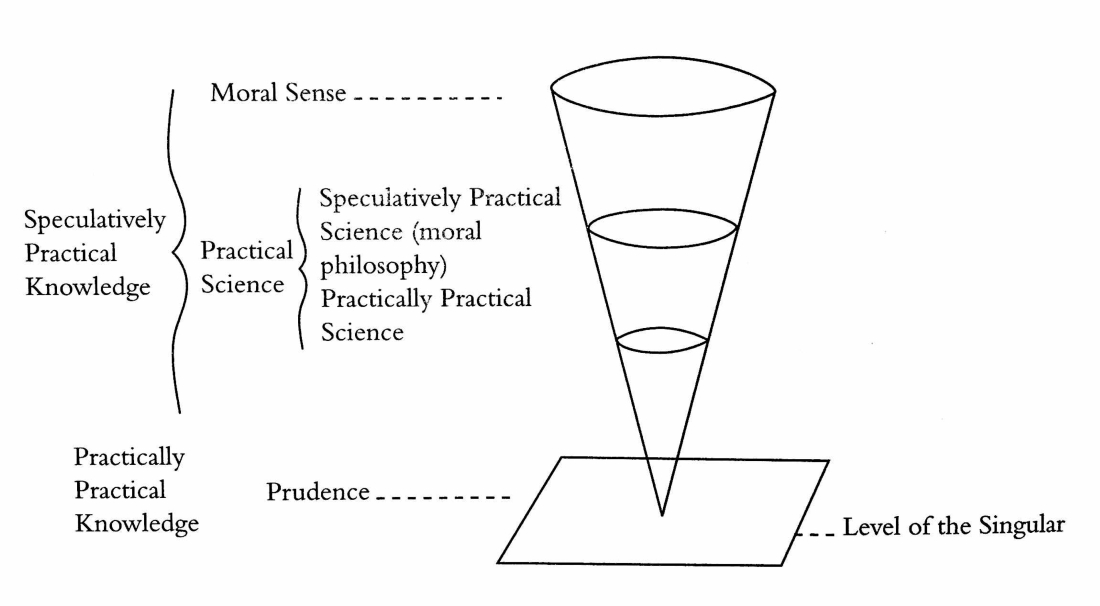

First, a background idea. In A Critique of Moral Knowledge (p. 42) Yves Simon provides a helpful image to keep track of the different epistemic levels at play when it comes to moral truth. Here is that image:

The inverted cone, beginning from the base and descending to the point that touches the plane below, represents the increasing practical, prudential specificity of moral knowledge. As one descends the cone, one approaches the level of the singular (where decision and moral action takes place). Thus the decreasing sizes of circles represent a couple of aspects of moral knowledge. First, they represent the increasing limitations of true practical propositions that could apply to possible individual circumstances (a loss of moral generality). Second, they represent an increasing need for prudence to judge whether and how the true general rule applies to the particular circumstance.

While Simon is by no means mathematizing ethics, the mathematical metaphor of the image is also helpful in this: there exists a potential infinity of smaller and smaller circles as one approaches the tip of the cone, so “ethical reasoning” of drawing smaller and smaller circles (analyzing an ethical situation in more exacting speculative detail) will never result in a decision, much less a correct decision. Hence the need for prudence, the virtue of seeing the moral truth in the concrete.

What is not depicted in Simon’s diagram are other “inverted cones,” or wider ones, that represent false conceptions of moral principles (in the broad sense—he’s thus including political philosophy). The assumption is that there is a generally true root moral sense, an objective natural law, the base of which is “Do good and avoid evil.”

Now, it seems that there is a twofold misunderstanding in Capizzi and Lewis’ essay. First, at which level of “the inverted cone” the discussion is taking place, and whether or not we’re debating about which “cone” is the truth. That is, Pecknold is suggesting that our political discussions “labor under” a false notion of the common good, that we have in mind various general and false notions of the common good—defective conceptions of the broadest “circle” that defines moral knowledge. Really, what results is a debate where the interlocutors are talking past each other, and the unspoken debate is really at which level of “the cone” the discussion ought to take place.

Thus, for instance, after their summary of the debate between Maritain and De Koninck, Cappizi and Lewis conclude that “it is difficult to see how it could be of much help to us now.” The debate’s details are interesting mainly to “Thomists, who labor over the fine points disputed and usually hold that De Koninck had the better of the exchange.” Now, this is true only by equivocating on the debate and its substance. One cannot conclude, then, that the substance “is of little consequence outside academia.” Once you do so conclude, however, this shifts the discussion down “the cone.”

Well, why is it of little consequence? Because “Maritain and De Koninck were both committed to the common good as relevant to political reflection, in at least the very general sense of calling citizens to regard the flourishing of the community as a whole as an appropriate end of politics.” However, this is a different sense of generality—a generality that means (as the essay goes on to admit) a general collection of competing concepts of the common good.

So, Capizzi and Lewis are talking past Pecknold. They mean different things by “debate the common good” and what it means to “reject the idea” of the common good. Pecknold is understanding the first more theoretically, they more practically and prudentially, and Pecknold is understanding the second in a more practical and prudential sense, and they more theoretically. Pecknold’s essay is a call to conversion at philosophical, theological, and personal levels, not a policy white paper in a government agency.

Thus, Capizzi and Lewis go on to ask how anyone could be against the common good understood in a “very general way” (because in that vague way, including both true and false conceptions, that is indeed impossible), such that to merely “invoke” the common good is “of limited political value” and “no problems are solved or policies recommended by saying, ‘but the common good!’” (because even invoking a true conception of the common good does not result in a practical decision, whether individually as a moral decision or collectively as a political action, because it’s “up the cone”), and that “nearly everyone … appeals to some notion of the common good” (indeed, even a band of robbers could do so). Thus also, they can observe that no politicians campaign on a platform that rejects the common good and that “most of our political debates, precisely insofar as they are political debates, are debates about the common good” (because nobody rejects the idea of the common good, and thus we debate about the means to reach the “thin” consensus or compromise conception of our competing general notions of the common good). Finally, because of this differing emphasis, it makes sense why they conclude that “Debates about philosophical fine points related to the concept of the common good are no substitute for analysis of which constitutional structures, laws, and policies best promote and protect the common good.”

By talking past Pecknold, however, Capizzi and Lewis give the appearance of also missing his point. That is, first, the theoretical aim was not accepting or rejecting the common good as a concept, but having the true theoretical understanding of the common good as an indivisible final cause of social order. (Indeed, even to make their own point, they have to propose a definition of the common good, which is unsurprisingly minimal and vague.) Second, the practical and prudential concern was not how the mere invocation of the common good circumvents the need for practical analysis of policies as means to common ends—and it is profoundly unclear that those proposing “common good” talk think that—, but about the decision to reject the true notion of the common good and its primacy over my private good. That is, the common good has a greater lovability and preferability to my private good that profoundly shapes (or misshapes, given the wrongheaded actions) personal decisions and the life of the political community. Even friendships are deeper when rooted in the true common good.

That Capizzi and Lewis are having a different discussion makes more sense when reading the final section of their essay (“Modern Societies and Secular States”), where they argue, in effect, that only a “thin” understanding of the common good is possible today in modern nations. Here, “thin” captures both the demands of pluralism and thus conceptions of the common good (“Any advocacy for the conception of the common good as ordered to God has to take that pluralism into account in a way, say, in which Aristotle and Thomas did not”) and the limits of solidarity at the national level (“But the diversity of modern societies and the character of the modern state require that the common good be necessarily thinner at the national level”). This effectively eliminates De Koninck’s proposal as a live practical or political alternative (that is, when one is hearing that proposal from far down the “inverted cone” of moral epistemology, amid a field of diverse, pluralistic “cones”.)

This “thin” common good, according to Capizzi and Lewis, fits with the Catholic Church’s “adoption” of “a more cautious and restricted view that seems appropriate to our own circumstances,” namely the definition proposed by Gaudium et Spes and repeated in many other “authoritative social teaching documents of the Catholic Church.” In Gaudium et Spes, the common good is defined as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment.” (This definition has been characterized as a more “instrumental” conception and adopted as the flagship definition of the New Natural Law theorists; see the debate between this and this article, for starters.)

However, here we begin to see a broader landscape of debates brought to light by the Cappizi/Lewis and Pecknold “debate”. The essays, at least when taken together, merely redraw old battle-lines and make no real advances.

First, modern nations are indeed limited in their ability to realize the true political common good. However, the recent debates over “post-liberalism” and even “integralism” have shown how easily one can call into question whether that means that the resulting common good pursued by a nation is really “thin” at all, and not, in actuality, a “thick” but false common good. Indeed, it is one of the corollaries of De Koninck’s little book that one cannot help but define for oneself and act according to—however distinctly or indistinctly conceived or ill-conceived—a substantive notion of the common good. (This is because to not seek God as the ultimate common good is to reject Him.) To rule out of bounds a “thick” concept of the political common good is to make a thick vacuum out of the thin common ground of the overlapping Venn diagrams of private conceptions of the good life.

Second, to return to those Thomists laboring over fine points about the common good: John Finnis (in Natural Law and Natural Rights, 2nd ed., p. 155) defines it as follows: “A set of conditions which enables the members of a community to attain for themselves reasonable objectives, or to realize reasonably for themselves the value(s), for the sake of which they have reason to collaborate with each other (positively and/or negatively) in a community.” (Note that Finnis clarifies the apparently overly-instrumental character of this definition of “the common good” in the postscript to the second edition; see p. 459.) Finnis derives this definition from the Fr. Delos, in his commentary to Somme thêologique: La Justice, t.1 (1948), p. 242: “. . . of the common good, that is, a part of that ensemble of social conditions thanks to which the individual will be enabled to fully develop. It is, indeed, that ensemble of social conditions which constitute the common good.”

Now, Delos’s proposal is at least materially similar to the definition of the common good in Gaudium et Spes. However, Pecknold is on to this too. His more recent First Things essay, “Deliver Us from Ideology,” is inspired by, among other things, Russell Hittinger’s lecture “Tradition or Pottage? Reflections on Catholic Social Teaching.” In that lecture, Hittinger notes that even the Compendium of the Church’s social teaching cannot help but include in apparent tension two apparently different notions of the common good (see The Compendium, n. 164). Pecknold labels them (a) and (b):

a. The common good indicates “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily.”

b. The common good does not consist in the simple sum of the particular goods of each subject of a social entity. Belonging to everyone and to each person, it is and remains “common”, because it is indivisible …

The first is the more “material” definition, the second is a more “metaphysical” one. The former could be characterized as a definition by effect, the latter as essential. The latter is, substantively, justice and peace—“the social and community dimension of the moral good.” The former is indeed, it would seem, a “cautious adoption” of the Church to the contingent historical realities of secular modernity’s inability to hold in common substantive metaphysical truths.

It is that inability that Pecknold is trying to address by way of invoking an old Thomistic debate about the primacy of the common good over the private good. However, the reason one might conclude that “invoking the common good under the influence of De Koninck, Maritain, or even Aquinas doesn’t advance the political conversation that characterizes a healthy polity” appears to be fundamental equivocations on what having a “political conversation” or a “healthy polity” means. A different conversatio and salus indeed.

It recalls the old sense of “politics” in Plato, and how harsh it sounds to modern ears: the art of caring for the soul.

2 thoughts on “Shorting the Market on the Common Good”